artist / researcher

Mygrations, 1999

Nien Schwarz

Introduction

The final chapter of my PhD exegesis describes the creation of Mygrations, a 4m2 collage made from ocean maps. Mygrations the collage is inseparable from Migrations, the piece of creative writing and illustrated story that I share below. In the written version I begin by visiting the collage the morning after my exhibition Beyond Familiar Territory opened at the Canberra Museum & Gallery in February 1999.

In reverse chronology, Migrations takes the reader through the three months preceding the exhibition opening, recounting in a journalistic manner the making of the collage in the Sculpture Studio at the Canberra School of Art during the hot Australian summer. Enrolled year-round, and unable to fly home to Canada for Christmas that year (Christmas in Australia is in summer), I was alone and had the main sculpture studio to myself. I could spread out. And I did.

The collage started out small, inspired by a Christmas hymn about peace on Earth. As a young child I firmly believed that by the time I turned thirty people would have learned not to wage war. The collage snowballed into something deeply personal; a lament for the Canadian arctic I missed, and a lament for my deceased father who had suffered terribly as a child in a World War ll Japanese internment camp 1942-45.

The collage was constructed from 170 duplicate topographic maps, rescued, along with thousands of other maps, from the National Library of Australia’s 1996 purge of paper assets. Printed in 1944 for war-time distribution in Australia, many of the maps are emergency editions with bright red instructions to hand in to the nearest military base or police station if found.

Mygrations An illustrated story about Mygrations 1999

Johannes Vermeer,

The art of painting, 1666-68

The history contained in the wall map was meant to inform domesticity as evidenced in Vermeer’s The Art of Painting. Svetlana Alpers

Canberra Museum & Gallery, 7:58 pm Thursday 18 February 1999

Last drinks. It’s been a heady night for which I bought a little black dress and even had my hair trimmed - the first time in Australia. Four years on, and my life is still punctuated with many firsts. The pitched clamour of the black-clad crowd at the opening of my exhibition Beyond Familiar Territory is fading into this perfect Persian blue evening. I feel strange, empty. I have no family here and no plans for the remainder of this evening.

Mygrations beckons. I cross the gallery to commune with her. Her sea of aquamarine and robin egg blue hovers off the wall, cascading to the floor from just below the gallery’s ceiling. Up close Mygrations is a meticulous patchwork of row upon row of small, overlapping, stamp-sized squares of ocean maps.

The perspective is aerial. Most of the collage is a vast expanse of blue, while far below we see, what could be, long rolling swells lapping the shores of a circular chain of tiny hilly islands. There's an uncanny sensation of floating: a vertiginous umbilical spiralling between Heaven and Earth.

The flanks of the collage sway gently to overhead air currents. I take it as a cue to focus on my breathing. Then whisper good night.

10:10 am Friday 19 February 1999

My exhibition Beyond Familiar Territory opened last night. The opening coincided with my 37th birthday and also marks the material conclusion to my doctoral studies.

My walk to the Canberra Museum & Gallery this morning is accompanied by a symphony of cicadas. Heat crackles underfoot, my toes are burning. The shadiest streets define my route. I’m looking forward to being the gallery's first visitor.

But someone's arrived before me and he's sitting directly in front of Mygrations. There's not supposed to be a sofa in front of this work. There wasn't last night, why now? The curator should have consulted me before placing furniture in my installation. I'm really cross.

I hover in the doorway of Mygration's dedicated exhibition space, assuming he’ll leave, his contemplation complete, or his reverie broken, so I can begin mine. But he doesn’t move a muscle.

Beyond Familiar Territory features multiple sculptures, all are outcomes of my

PhD candidacy and discussed in my exegesis. The chapters in my dissertation

are intended to be published separately. All up, probably 60,000 words. Next month, here in the gallery I face three external examiners to defend my thesis.

I am the Australian National University’s first PhD candidate in Visual Arts. As yet there are no goal posts for this degree. The terms practice-led and studio-based research I will not hear for a while yet.

Mygrations is a work through which I diverted spectacularly from my thesis objectives of researching relationships between minerals, mapping, mining, consumerism, and contemporary art. In summary, I examined how artists respond to mining and associated ecological and political issues. I researched the works and writings of Robert Smithson, Alfredo Jaar, and the painters of the Yolgnu Bark Petitions who protested bauxite mining on their ancestral lands.

Mygrations summoned me and it consumed me. There was no plan to make this massive collage - it evolved from deep within. I didn't have time to make it, but

I did. Its relevance to the research question is unclear. A spectacular diversion!

The intensive process of cutting and pasting small (3cm2) fragments of duplicate Pacific Ocean maps on a huge canvas was physically exhausting. When I could

not bear to exclude it from this exhibition, we built a dedicated room for it.

Looking around at the other works in my exhibition I realise Mygrations is an island, and about being an island.

The man still occupies the bench. I tip toe past him and perch at the far end to scribble my thoughts. I wonder if he's irritated by this horribly scratchy 2H pencil?

Minutes pass. I'm mystified by his immersion. I peak at his profile. He could be in his late thirties. Long fingers clasped under a long thin face remind me of an El Greco figure. His eyes sweep across the collage, slowly east to west, then north to south. The rest of him doesn't move. I really don’t know to think because most artworks are lucky to get a cursory glance.

He rises swiftly. Tripping over my words I blurt "what do you think about this artwork?” I catch him mid-stride. He stops in the doorway, that liminal space between in here and out there.

I can't believe I said that! Oh my god, what if he's an art critic? What an idiot I am!

He turns around, slowly, and walks right up to the collage. He traces two small circles (first clockwise, then anticlockwise). Good for you I think, touching my work. Sharply craning his neck, he scans the upper reaches. I'm impressed how the collage dwarfs him; in fact, I'm immensely pleased.

He ever so lightly strokes the surface with the back of his left hand – one long slow sweep. Mygrations ripples in reply.

My question hangs between us. I'm deeply uncomfortable and turn my attention to his feet. I gasp. He’s wearing white runners! Clearly he isn’t local, but an import, like me.

Exhaling heavily, and with his back to me, he responds in an utterly predictable North American accent “homelessness”, and after lengthy pause “no permanent place”. Then walks out.

He didn't once look at me, but I have just been x-rayed 1000 times. I get up and stroke the work too. Tears wet my dusty toes. Did you know our tears are as salty as the oceans?

...what the collage-piece unravels from the surface of the canvas..., is after all, the flight coupon we thought we had lost. Marjorie Perloff

Boxing Day 1998

It’s burning hot. The most bearable place, if not in Canberra's Tuggeranong shopping malls, is here, on the sculpture studio floor.

I’m restless. This collage is taking ever so long to make! I'm worried I won't finish it in time for my exhibition in February.

I’m sitting on this canvas of about four-square meters. I made it by sewing together two lengths of calico. I’ve done my best to keep the stitching flat, yet there is central suture, a spine, a backbone.

I shift every few minutes because my legs get in the way of my brush, or my feet fall asleep. I cross one leg, sometimes both, or tuck them beneath me. Other times I stretch my ridiculously long legs straight out in front, or I lie curled on my side. Most of my life is spent living off the ground - in cars, chairs, beds, and at desks in boring institutional offices. I think of desert painters sitting on the ground, their ground, sitting on their stories.

I’ve done five hours today; repeatedly carefully choosing a square of blue map and delicately pasting it onto the cotton ground, just barely overlapping each one with its neighbours.

Except for the occasional screech of gang gangs and sulphur-crested cockatoos it is almost silent. In Canada my mother will be listening to Christmas hymns on CBC FM, while a turkey roasts to golden perfection. She’ll serve apple, sage and wild rice stuffing in the oval Wedgewood bowl, and cranberry sauce in her mother’s

long-stemmed crystal bowl. Silverware glistens gold in candlelight. I hum Silent Night and lose myself in an endless sea of blue maps down under.

With every few pieces I paste into place my mind wanders north and south of the Equator, in between the accounts of arctic explorers in the north and the south Poles, and what I know of my family's history in France, Indonesia, The Netherlands and more recently Canada. My father’s family were Huguenots. Persecuted in France they fled north to the Netherlands.

I recall my maternal grandmother’s stories of raising her three daughters during and after the war, and my mother's stories of migrating to Canada by ship in the 60s, and the night she was so seasick she lost hold of me in a big swell. My mind

is a spinning compass.

Geography of the land is probably to a large degree geography of the mind.

Svetlana Alpers

A poster-sized picture-map of the world hangs above my childhood bed. The original was painted in watercolours for the oceans are translucent currents of cool blues and warmer turquoises, while the deserts bleed yellow and red sand. The map has a plain white border, which I imagine keeps Earth from spilling into space.

Different countries and cultures are identified through a smattering of iconic animals and people of different colours and in different styles of dress. I see painted forests and mountain ranges, and in some places houses in which people live, including an igloo, a patterned tee pee and straw and mud huts. I search for a brick house on a hill overlooking a river.

Canada, our new home, is a vast, snow-and-tree covered expanse. Furry animals, including moose, beavers, wolves, and various kinds of bears, are strung out across the land. It gives me great satisfaction to associate my adopted country with these majestic wild mammals.

I can’t see anything marking my birthplace. Possibly it is too small to fit anything about it on this map, but really, there should be a windmill. My young heart knows it was not a Dutch artist who originally painted this map of the world.

From the vantage point of my homemade wooden bed, innumerable journeys

take me across treeless deserts, through thick and thinning clouds, over polar

and tropical seas. I circumambulate the North and South Poles. I never get tired

of travelling, and I’m always in my own company. Where there is water I cross in

a wooden boat with a single red sail.

My six-year-old self, standing on my bed, traces a watery route between The Netherlands, Indonesia, and Canada. I have an Indonesian grandmother, who claims to be Portuguese, but have met her only twice as she is my paternal grandfather’s second wife. I fantasize being on Java and join my father, his little brother, and my Oma to help them survive the WW ll Japanese prisoner of war

hell camps for colonial European women and children.

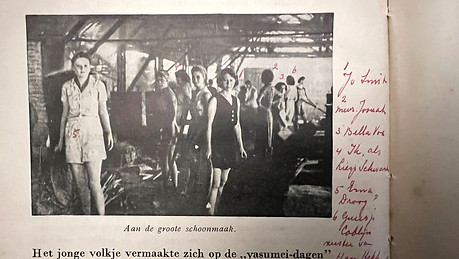

Sketch by Mrs Vogelaar-Weber printed in Het Verbluffende Kamp by Ko Luijckx, 1945

I beg Papa to share a memory. I understand he doesn’t want to remember because it still really hurts, and I know he wants to protect me. From a very young age I understand that some people enjoy being terribly cruel. But sometimes he relents and tells me one of two stories, only ever the same two.

One story goes along the lines of plugging fistfuls of dirt, and on one occasion a piece of fruit, far too rotten to eat, in the exhaust pipe of a Japanese military jeep. Watching the mess shooting out when the engines started was thrilling. The other story is about a dog collapsing from inhaling knee-height volcanic gases. I can’t remember if this happened in the POW camp.

I fear a recurring nightmare. My father is in danger. I must save him. I’m running towards him, but tall dark trees always close in, obscuring him from my view. By the time I get to where I last saw him, standing alone on a little wooden bench in a clearing, surrounded by a ring of trees, he is gone.

On the rare occasion that Papa and I shop together, he sometimes pauses at small piles of imported exotic fruit. How bizarre these foreign fruit look, and so out of place in Canada a country regularly in the grip of minus degree temperatures and meters of snow. He carefully picks up some variety of fruit nameless to me. There is silence. I look at his beautiful slender fingers, too afraid to look at his face because I know this routine all too well. I hold my breath.

The oddly coloured, prickly or pocked fruit sits in his cupped hands. Then I see him, and I hate this vision, of Papa age nine, with big ears, skinny legs and swollen knees, ravenously devouring a tropical fruit highly past its prime. I can only imagine the three years of hunger he endured. How many of his little friends and their mothers died around him when he was my age?

Standing there in the supermarket my chest feels like it will explode with anger and sadness. I hate war, I hate it, I hate it all! Faster and louder my heart thumps in my head. I’m afraid he will hear my panic, but I must be strong for him. Wil je dit probeeren? he asks.

I can never decline to share an overly bitter or sickly pungent sweet fruit. I don't like these exotic fruits that have been picked far too early. I say yes, secretly hoping he’ll then share a different Indonesia story. He never does though, only the two stories about stuffing the jeep’s exhaust pipe with crap, and the collapsing dog. He never talks about the 3 years in hell. Not even with Mama.

Photo printed in Het Verbluffende Kamp by Ko Luijckx, 1945. My grandmother wrote the red note in the margin “This could have been Erik, he looked precisely like this.”

It’s too hot. The acrylic medium dries on my brush. Sweat mingles with a few tears. Papa, Indonesia, and the bedroom picture map I loved so much slip away.

I’m having trouble piecing together the western shore of an island. I keep searching for an appropriate piece of map, but I can’t find one. I put this island aside and start afresh, this time beginning with a northern edge.

Martin van Kranendonk’s geological mapping camp, Labrador coast, July 1992

One excuse for lighting up is that life is so incredibly healthy up here that I just need to do something unhealthy. My other excuse is that smoke keeps mosquitoes at bay. At dawn this morning they were hitting the tent, no pounding is more like it - like rain. I was almost fooled into putting on my raincoat before emerging from my downy nest. Yesterday, with one slap of the hand, we counted 121 mosquitoes!

I heard from a local pilot about a man and woman who died last year after their canoe capsized. They died from exposure to blood sucking insects, not from lack of food or hypothermia. I’m reminded of the time 11 years ago in the western Arctic when I got lost and went to the edge of insanity for a few minutes, screaming and running in circles, because the mosquitos and blackflies were so bad when the wind suddenly dropped. I tried to take a short cut back to camp because I was late heading back to make dinner. I ended up losing time and energy slushing about in boggy tundra. I had a map but had trouble holding it because of the feasting on my fingers. My temporary derangement scared me more than anything. I have learned. To survive requires presence of mind. Always keep your wits about you Nien. Easier said than done, that’s for sure.

I sit quietly in the doorway of my canvas home - matching the stillness of an Arctic summer day. There’s not a breath of wind or any movement. My outstretched legs rest on gravel and lichen. I feel a small sharp rock protruding through the tent floor and shift slightly, to the right.

I have a third excuse for smoking. I hardly draw on the cigarettes, but I light one after the other. My ears are pricked, I constantly scan for any movement around me. Across from where I’m sitting are breathtakingly beautiful ice floes, glinting in the sun. This island-studded expanse of sapphire-blue Arctic Ocean sweeps east towards Greenland. From the helicopter I can sometimes make out the distant shores of Baffin Island. I love this country. It is painfully beautiful, and also very dangerous.

I’m almost too afraid to move. I feel silly. It’s such a gorgeous arctic summer morning, but I mustn’t be disarmed by that. I have every reason to be afraid. As much as I hate guns the cold steel against my thigh is reassuring. For a moment I wish for safety on one of those islands, out there in the icy blue ocean, but that’s no help. There are polar bears out there too.

I chastise myself for my fear, but the memory of being charged by a grizzly bear ten years ago on a similar geological expedition is still fresh. Only 12 hours ago I felt the same as I did back then. At about 1:00 this morning our pilot woke up the camp with a blood-curdling cry. Don’t worry he’s fine. But where did that polar bear go?

The bastards, they’ve left me alone, here in camp with 2 freezers of meat and I have my period.

18 December 1999 (my 7th wedding anniversary)

One frustration leads to another. I can’t find a square of the darkest turquoise and I really need a dark anchoring point in this last corner of this island. Half of the collaged map is completed.

So far, it’s taken 170 topographic maps cut into 3 cm squares. I think back to the previous two years and how every time I felt terribly out of sync with being in Australia, fragmented by the distance between here and my loved ones in Canada or Europe, I tore or cut maps into little squares. Then I’d join them together to form a new cloth, a tablecloth, a new kind identity, an imaginary land.

I’m creating Mygrations from maps printed in 1944 for wartime distribution in Australia. These maps cause me to reflect on tensions between different parts of the world and my life-long utopian desire for no more war. I look at the large circle of broken islands emerging, like steppingstones and wish people would realise the many ways we are all connected.

I think back to my experiences of working with international artists in the National Gallery of Australia’s 1996 exhibition, Islands. I delighted in exercising my French with Annette Messager and Christian Boltanski. I found it remarkable how at ease Boltanski was in developing a new work in situ in response to an unfamiliar space.

I assisted Thai artist Montien Boonma with constructing his herb and spice encrusted temple-like structure. Montien, his friends and Thai Embassy staff in Canberra introduced me to Buddhist principles and Buddhism in contemporary arts. I recoiled in horror at the first-hand experiences of Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar and his absolute disillusionment with the West and the United Nations for not preventing the highly preventable genocide in Rwanda. I imagined the thoughts

of German artist Joseph Beuys whose wartime experiences surely haunted his felt pieces we hung in the gallery. I mustered up the courage to give Australian artist Lyndal Jones a hug, because she really needed one.

In the centre of my map there is only a vast expanse of blue. Here, not even the tiniest island emerges on which to locate a sense of place.

instead of finding reassurances...one is forced to advance beyond familiar territory... Michel Foucault

The intensity with which I approach the cutting and pasting of maps recalls my immersion in the colouring of geological maps in the Canadian Arctic field camps so many years ago. The process of making this collage is probably about escaping reality through memory. And by weaving together fragments, finding something lost, something new, or hidden. In the Arctic the intense and precise colouring of geological maps distracted me from worrying about roaming bears, feeling the cold, the intensity of smoke from forest fires billowing in from the south, and the bloody hordes of mosquitoes and black flies.

I often look at a postcard reproduction of Jan Vermeer’s painting of Woman Reading a letter, 1663-64. During my many years of cooking along the fringes

of arctic shorelines we all yearned for the arrival of the mailbag dropped off by

a plane every two - three weeks, along with supplies of food. I loved to receive a letter, someone else’s thoughts I could absorb slowly, over, and over, in my own time. I think back to the thousands of letters I have written in the quiet moments

of endless 24-hour daylight days, when icebergs twinkle in the distance, the ocean lies as flat as a mirror, islands and clouds impossible to separate from their reflections, and the momentary splash of a narwhale slicing through still waters spouting for air.

I try to explain in my letters what silence is like, and of my near silent excursions in the canoe, loving the feel of my hands and paddle slicing through freezing ocean, lake, and river waters. I try to explain in my letters what it is like to be alone all day, in the so-called middle of nowhere. To work with Earth scientists who also love their work, and on their return to camp in the evenings, over dinner, endlessly discuss the formation and age of the Earth in billions of years and draw what

they saw today on the plastic tablecloth. In my letters I describe my joy at walking endless shorelines, in the tracks of bears and wolves and caribou, and at the interface of land and water where the Inuit people still draw sustenance. In my letters I share daily menus and my experiments with cooking in bush camp conditions.

But I know that unless you’ve been to this kind of place - where you are humbled by silence, the spirit of all things, and you're cognisant of not being invincible - you won’t understand my letters, because they are slow and very detailed.

4. Ik als Liesje Schwarz. Printed in Het Verbluffende Kamp by Ko Luijckx, 1945

I treasure a book handed down to me by my mother. It was written by a survivor

of the Japanese prisoner of war camp in Java that my father endured with his mother and his little brother for almost three years, 1942-45. In the book is a photo of my grandmother. It’s hard to make out, but I think she’s wearing a floral-patterned dress.

I always meant to ask, but forgot, and then it was too late, what my father remembered of his journey from war-ravaged Indonesia to war-ravaged Europe and what kind of ship it was that carried him across so many lengths of ocean. Perhaps there lies a clue in his last drawing - a ship I had asked him to sketch

when we both knew he was dying. Sadly, I’ve lost Erik’s drawing, but I remember

it through the making of this collage.